The Igloo Tag is a vital mark of authenticity for Inuit art, but it’s only the starting point of responsible collecting.

- True authentication involves understanding the cultural vocabulary of the art and researching the artist’s specific community affiliation.

- An artwork’s long-term value is driven more by the artist’s reputation and story (its provenance) than by the physical medium.

Recommendation: Shift your mindset from a consumer searching for a sticker to a connoisseur engaging with the artist’s narrative and the economic ecosystem that supports them.

For many travellers and art collectors in Canada, bringing home a piece of Indigenous art is the ultimate souvenir—a tangible connection to the land, its history, and its original peoples. You hold a carving or a print, feeling its weight and admiring its lines, but a nagging question surfaces: is it genuine? In a market flooded with imitations, the desire for authenticity is more than a preference; it’s an ethical imperative. The common advice is to “look for the Igloo Tag” or avoid anything that seems too cheap. While this is a crucial first step, it barely scratches the surface of what it means to be a responsible and informed patron of Indigenous arts.

Relying on a single sticker, however important, reduces a complex cultural and economic ecosystem to a simple transaction. It overlooks the rich diversity between First Nations, Métis, and Inuit art forms, and the powerful stories embedded in each piece. But what if the process of authentication was not a fearful hunt for fakes, but a rewarding journey into connoisseurship? What if the key wasn’t just identifying a tag, but learning to read the cultural vocabulary of the art, understanding the systems of trust that support artists, and appreciating the provenance as part of the work’s soul?

This guide moves beyond the checklist mentality. We will explore the symbolic language of iconic figures like the Raven and the Eagle, detail the practical steps for verifying an artist’s community ties, and compare the investment potential of different mediums. By transforming your approach, you will not only acquire a beautiful piece of art but also become a meaningful participant in the preservation and flourishing of Indigenous culture and economic sovereignty. This is your path from souvenir hunter to a true, knowledgeable collector.

To guide you on this journey from consumer to connoisseur, this article breaks down the essential knowledge needed to navigate the world of Indigenous art with confidence and respect. Explore the topics below to build your expertise step by step.

Summary: How to Identify Authentic Indigenous Art in Canada: Beyond the Igloo Tag

- Why does the Raven hold a different meaning than the Eagle in West Coast art?

- How to research an artist’s community affiliation before buying?

- Serigraph or cedar: which investment holds its value better?

- The souvenir shop scam that hurts Indigenous artists

- How to pack a soapstone carving for a flight home?

- How to buy mukluks or jewelry from verified Indigenous designers like Manitobah Mukluks?

- Classic collection or contemporary edge: which gallery anchors your art trip?

- How to read the hierarchy of figures on a totem pole correctly?

Why does the Raven hold a different meaning than the Eagle in West Coast art?

To the untrained eye, the powerful forms of a Raven and an Eagle in Northwest Coast art might seem like interchangeable symbols of the wild. This assumption, however, misses the rich cultural vocabulary that is the first pillar of true art connoisseurship. These are not mere decorations; they are distinct characters with deeply defined roles in cosmology and law. Understanding their differences is the first step in learning to “read” a piece of art rather than just look at it. The Raven, for instance, is a complex figure, often a Creator or Transformer, yet also a trickster. According to Haida law, it was Raven who discovered humankind in a clamshell, a foundational act of creation. This duality of being a creative force that is also mischievous and self-serving is a central theme.

The Eagle, by contrast, occupies a different spiritual and social space. While the Raven is often the messenger of the Creator, the Eagle acts as the messenger of the people, representing a bridge between the earthly and the divine. It symbolizes power, vision, and prestige, often associated with leadership. Visually, their distinctions are just as precise. The Eagle’s beak is defined by a prominent, sharp curve that curls downward toward its body. The Raven’s beak, on the other hand, is longer, straighter, and has an almost squared tip. Appreciating these nuances is fundamental. It moves you beyond a surface-level appreciation and into a deeper engagement with the artist’s narrative intent and cultural context.

How to research an artist’s community affiliation before buying?

Once you begin to understand the cultural vocabulary, the next step in your due diligence as a collector is verifying the artist themselves. An artwork’s authenticity is inextricably linked to the creator’s identity and their connection to their community. This is where systems of trust become your most valuable tool. The most famous of these in Canada is the Igloo Tag Trademark, managed by the Inuit Art Foundation. This tag, affixed to a work, certifies that the art was made by an Inuk artist. It includes the artist’s name, their community, and often the work’s title and creation year, providing a direct link to its origins. A license number on the tag identifies the authorized distributor, creating a traceable chain of provenance.

Your research shouldn’t stop at the tag. The Inuit Art Foundation maintains an invaluable online artist database featuring profiles of historical and contemporary artists. Cross-referencing the name on a tag with this database is a crucial verification step. Beyond the tag itself, the economic impact of this system is profound. A formal study confirmed that consumers are willing to pay an additional $117 on average for pieces sold with the Trademark, injecting millions directly into the Inuit arts economy annually. This is economic sovereignty in action. When you buy a certified piece, you aren’t just acquiring an object; you are upholding a system designed to protect and empower artists.

This process of verification—checking the tag, researching the artist, and understanding the authorized channels—is the core of a connoisseur’s due diligence. It transforms the act of buying from a guess into an informed decision, ensuring your investment supports the correct artist and community. Authorized distributors include major co-operatives like La Fédération des coopératives du Nouveau-Québec (FCNQ) and Canadian Arctic Producers (CAP), which have been foundational to the development of the market.

Serigraph or cedar: which investment holds its value better?

A common question for new collectors is whether to invest in a unique carving or a limited-edition print. From a purely logistical standpoint, a serigraph (silkscreen print) is easier to transport than a fragile soapstone or cedar carving. But when considering long-term value, the medium is secondary to a much more powerful factor: the artist’s provenance. The reputation, story, and exhibition history of the artist are the primary drivers of an artwork’s appreciation. A piece’s value is not in its material, but in its narrative.

Artist Provenance as Primary Value Driver: The Kenojuak Ashevak Example

The investment value of Indigenous art depends more on the artist’s reputation than the medium. A limited-edition print by a master artist like Kenojuak Ashevak, whose works are held in major museums worldwide, can appreciate significantly more than a carving by an unknown artist. As noted in materials related to the Kenojuak Ashevak Memorial Award, this legendary artist’s prints command premium prices in the secondary market. This demonstrates how an artist’s legacy, built over a lifetime and recognized by institutions, is what truly drives long-term value, regardless of whether the work is on paper or carved from stone.

This principle doesn’t mean the choice of medium is irrelevant, but it reframes the decision. A carving is a one-of-a-kind object, while a print’s value is tied to the scarcity of its edition. Both require proper authentication, like an Igloo Tag and documentation. For a collector, the practical considerations of cost, transport, and insurance are important, as detailed in the comparison below. However, the most strategic investment is always in an artist whose story and work are recognized and respected within the established systems of trust.

| Investment Factor | Limited Edition Serigraph | Cedar Carving |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Cost | $500-$2,000 | $1,000-$10,000+ |

| Transportation | Tube carry-on friendly | Special shipping required |

| Insurance Needs | Standard homeowner’s | Specialized art insurance |

| Authentication | Edition numbering + Igloo Tag | Igloo Tag + provenance docs |

| Market Premium | $117 average with certification | $117 average with certification |

| Storage Requirements | Flat file or frame | Climate-controlled display |

The souvenir shop scam that hurts Indigenous artists

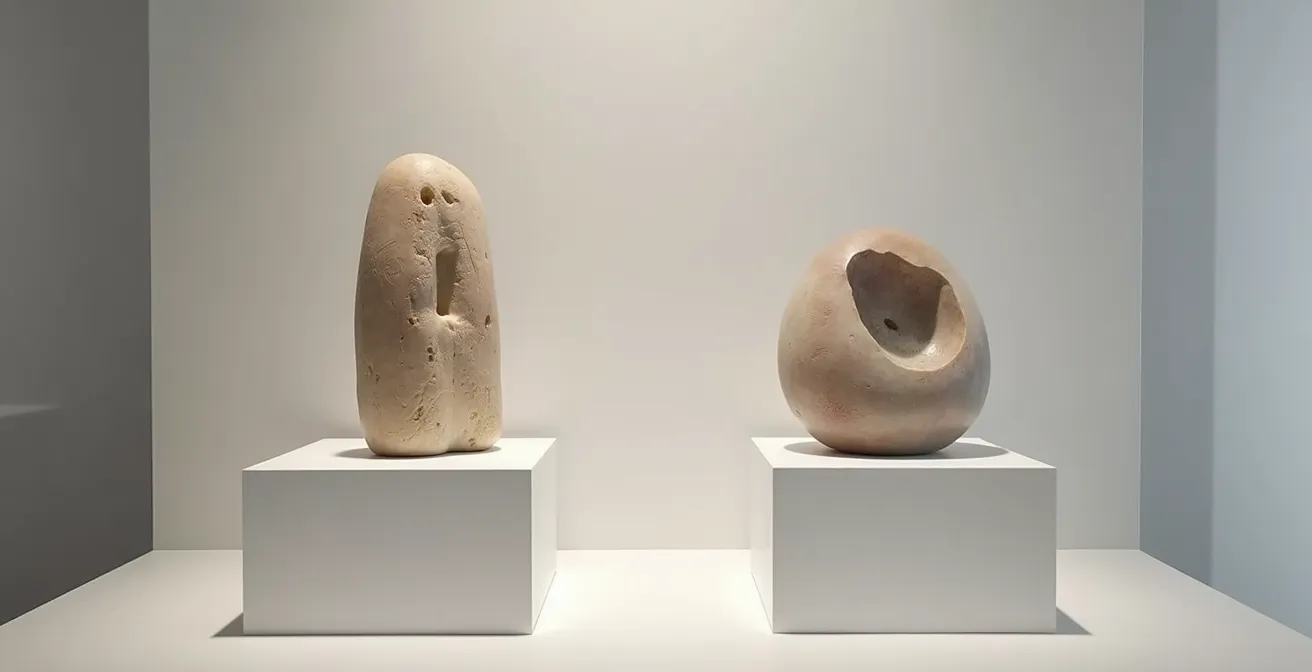

The market for authentic Indigenous art is constantly undermined by a flood of mass-produced fakes and culturally appropriated designs, often found in tourist-heavy souvenir shops. These items not only deceive buyers but, more importantly, they divert income from Indigenous artists and communities, causing direct economic harm. Some estimates suggest that as much as 80% of Aboriginal-style art and giftware sold in Canada has no connection to Indigenous peoples whatsoever. This practice, often called “knock-off art,” is a significant problem that requires vigilance from consumers. While Canada has laws against misrepresentation, enforcement can be challenging, placing the onus on the buyer to be discerning.

Spotting these fakes requires a critical eye. Mass-produced items often have tell-tale signs: suspiciously low prices, a lack of artist information (name and community), or “Made in China” stickers hidden on the bottom. In British Columbia, the Authentic Indigenous labeling system was launched to help consumers identify work made by BC Indigenous artists, acting as a regional counterpart to the Inuit-specific Igloo Tag. When in a shop, always ask the staff directly about the artist and how they are compensated. Ethical retailers who work with licensed designs or buy directly from artists will be transparent about their sourcing and royalty agreements.

The difference between a hand-carved piece and a resin imitation becomes obvious upon close inspection, as seen in the comparison above. An authentic work will show the subtle imperfections and unique character of the artist’s hand, while a molded fake is often too perfect, too uniform. By choosing to buy authentic, you are not only getting a piece with a real story but are actively rejecting an exploitative industry and redirecting funds back to the creators and their communities.

How to pack a soapstone carving for a flight home?

You’ve done your due diligence, found a beautiful, authentic soapstone carving, and made the purchase. Now comes the final challenge: getting it home safely. Soapstone is a soft, heavy material that is notoriously prone to scratching and breaking if not handled with extreme care. The moment you leave the gallery, you become the steward of this artwork, and proper packing is a non-negotiable part of that responsibility. It is a meticulous process, but one that ensures your investment arrives intact.

Do not rely on a single layer of bubble wrap and a prayer. The professional method involves double-boxing and using specific materials to protect the delicate surface and protruding details of the carving. This may seem excessive, but it is the standard for a reason. Airlines like Air Canada and WestJet will accept fragile art as checked baggage, but only if it is properly packed and declared. Taking these steps not only protects the piece but also demonstrates respect for the artist’s work.

Your Action Plan: Packing Guide for Soapstone Art

- Gather Materials: Purchase necessary supplies from a store like Canadian Tire or Shoppers Drug Mart. You will need acid-free tissue paper, plenty of bubble wrap, packing tape, and two sturdy cardboard boxes (one larger than the other).

- Document Everything: Before wrapping, take detailed photos of the sculpture from all angles. Keep all purchase receipts and the official Igloo Tag documentation with you for insurance and customs purposes.

- Protect the Surface: Wrap the entire sculpture first in several layers of acid-free tissue paper. This creates a soft barrier that prevents the bubble wrap from leaving imprints or scratching the polished soapstone.

- Cushion with Bubble Wrap: Add multiple, generous layers of bubble wrap around the tissue-wrapped piece. Pay special attention to fragile, extended parts, ensuring they are well-padded and supported.

- Execute the Double-Box Method: Place the wrapped sculpture snugly in the first, smaller box, filling any empty space with additional padding (like more bubble wrap or crumpled paper). Then, place this box inside the second, larger box, ensuring there is at least two inches of padding on all six sides.

Finally, it’s wise to obtain a formal statement of value from the gallery where you purchased the piece. This document should include the artist’s name, community, and authentication details, which can be invaluable for both insurance claims and customs declarations upon your return home.

How to buy mukluks or jewelry from verified Indigenous designers like Manitobah Mukluks?

The principles of authenticity extend beyond gallery walls to wearable art like mukluks, moccasins, and jewelry. Here, the marketplace becomes even more complex, presenting different models of Indigenous enterprise. The informed collector understands these distinctions and makes purchasing decisions that align with their personal values. On one hand, you have internationally recognized, Indigenous-owned companies like Manitobah Mukluks. These businesses provide significant employment opportunities, help revive traditional skills on a large scale, and act as powerful platforms for Indigenous storytelling in the global market. Buying from such a brand supports a corporate structure dedicated to Indigenous economic development.

On the other hand, there is the option of buying directly from individual artists or smaller artist cooperatives. This can happen at a powwow, a local market, a community art centre, or through an artist’s personal website. This model provides immediate, direct economic benefit to the creator and their family. It offers a different, often more personal, connection to the art. Neither model is inherently “better” than the other; they represent different but equally valid strategies for Indigenous economic sovereignty and cultural continuity. As a CARFAC resource on Indigenous protocols notes, these initiatives are part of an ongoing effort to strengthen respect for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis artists and their rights.

When purchasing from any source, the key is transparency. A reputable Indigenous-owned brand will be proud of its story and its artist partnerships. An individual artist will be able to speak about their materials, their techniques, and their community. The savvy buyer learns to recognize and respect these different channels, understanding that each purchase contributes to a larger ecosystem of cultural and economic resilience in its own way.

Key Takeaways

- Authentication is an active process of due diligence—researching the artist and their community—not a passive search for a sticker.

- An artwork’s primary value is driven by its provenance: the artist’s story, reputation, and recognized legacy.

- Buying authentic Indigenous art is a meaningful contribution to artists’ livelihoods and the broader goal of Indigenous economic sovereignty.

Classic collection or contemporary edge: which gallery anchors your art trip?

With a foundational knowledge of symbols and verification, you can begin to curate your own art experiences. A trip to a city like Vancouver, a major hub for Northwest Coast art, can be tailored to your specific tastes. Do you gravitate towards the foundational masters who defined the art form, or are you more excited by the contemporary artists who are pushing its boundaries? Answering this question allows you to build a focused gallery-hopping itinerary. For a collector, this is where connoisseurship becomes a joyful, personal pursuit.

A “classic” route might start at the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art to immerse yourself in the work of a Haida master. From there, you could visit the Inuit Gallery of Vancouver to see works by established sculptors and printmakers, followed by a trip to the Museum of Anthropology at UBC for deep historical context. A “contemporary” route, in contrast, could begin at a gallery like Fazakas, known for showcasing emerging and mid-career Indigenous voices, followed by a scheduled studio visit in East Vancouver’s artist district. At every stop, your due diligence remains key: look for Igloo Tags, ask about an artist’s cooperative affiliations, and check if the gallery is a member of a reputable body like the Art Dealers Association of Canada (ADAC).

This act of seeking out, verifying, and collecting art is deeply connected to a larger story of cultural self-determination. It’s a story about Indigenous peoples reclaiming control over their narratives and their art. As Bryan Winters of the Inuit Art Foundation stated when the organization took over the Igloo Tag from the Canadian government:

It has been the goal of every Inuk in Canada to determine for ourselves who we are and how we are represented

– Bryan Winters, Inuit Art Foundation statement on Igloo Tag transfer

How to read the hierarchy of figures on a totem pole correctly?

Perhaps no symbol of Indigenous art is more widely recognized—or more profoundly misunderstood—than the totem pole. The common English phrase “low man on the totem pole” has cemented a false and colonial idea that the figures are arranged in a hierarchy of importance. This is the final myth a true connoisseur must unlearn. The figures on a pole are not a ranking; they are a narrative. They tell a story, document a family’s lineage, commemorate a significant person, or display the rights and crests a family holds. Position does not signify rank. A figure at the bottom may, in fact, be the most central character in the story being told.

There are different types of poles for different functions: house frontal poles that welcome visitors and proclaim a family’s identity, memorial poles that honour an individual, and mortuary poles that might contain the remains of the deceased. Each follows specific narrative conventions unique to the Nation and family that commissioned it. The figures, such as a Raven whose feathers were turned from white to black after he flew through a smoke hole to deliver light to the world, are characters in these epic stories. These poles were traditionally left to stand in the soil, returning to the earth naturally, a stark contrast to the colonial practice of removing them for museum collections.

The only way to truly understand a totem pole is to learn the oral history that accompanies it, ideally from an Indigenous knowledge keeper from the local Nation. Visiting places like Stanley Park in Vancouver or the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, which offer Indigenous-led interpretation programs, is a respectful way to begin. Approaching these monumental works with the understanding that they are complex visual texts, not simple ladders of power, is the final and most crucial step in shifting from a passive viewer to a respectful and knowledgeable observer.

Now that you are equipped with this new perspective, your journey can truly begin. Start by visiting a recommended gallery, a museum, or a certified online source not just to look, but to see. Engage with the art, ask questions, and build your collection with the confidence of a true connoisseur.